It's The End Of The World, As We Know It...

Date: 17/11/2014

Movie Review

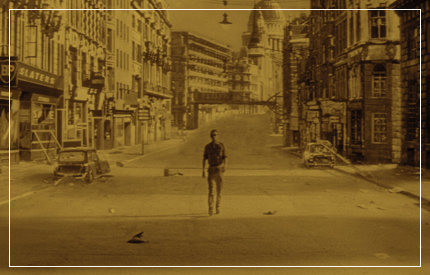

As part of the British Film Institute's Sci-Fi: Days of Fear and Wonder season exploring the outer realms of human imagination, 17 November sees the remastered, DVD release of Val Guest's apocalyptic The Day The Earth Caught Fire (1961).

A team of journalists at London's Daily Express are struggling to get to grips with a sudden and dramatic shift in the world's climate, following the testing of nuclear bombs by the American and Russian governments.

Washed-up alcoholic Peter Stenning, played by Edward Judd, and Bill Maguire, played by Leo McKern, are two reporters at the paper who attempt to get the story behind the phenomenon.

Stenning begins an infatuated relationship with Jeannie Craig, a secretary at the Meteorological Centre, played by Janet Munro. Using Jeannie as a spy, the newspaper discovers that the recent bomb testing has not only changed the Earth's tilt, affecting the world's climate zones, but has sent the entire planet hurtling towards the sun.

As mist descends on London town and the Thames begins to dry up, the journalists at the Daily Express, along with the rest of the world, must put their faith, and the future of humanity, at the hands of the scientists and experts who caused the catastrophe in the first place.

The Day The Earth Caught Fire excels as a cautionary tale about the desire for mankind to outdo nature, and the subsequent catastrophes that often befall such hubris.

Given that the film was released at the beginning of the sixties and around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, it is clear The Day The Earth Caught Fire was influenced by European anxieties of nuclear fallout caused by two warring superpowers, but also a more general scepticism about the right of humanity to meddle in natural forces that it doesn't truly understand.

Where the film perhaps falls flat, however, is in a quite-unavoidably male-centric perception of the world. Female characters seem only to perform secretarial duties at best; passing on information from man to man and rarely acting as knowledgable, independent people in their own right. Terms like 'sweetie' and 'dear' are used a little too often for comfort, while Janet Munro's character Jeannie is subjected to more than a few comments about her appearance that would today be considered downright sexist.

Chauvinism aside, the film gives an interesting and authoritative glimpse into the workings of Fleet Street hacks and print newsrooms at the beginning of the sixties, as the majority of the action and revelations are seen through the eyes of the journalists reporting on them. The dialogue is appropriately fast paced, as witty comment follows witty comment with the regularity of an Oscar Wilde comedy, if without the charm.

Part of the film's journalistic authenticity probably stems from the fact that the part of Jeff, the editor, is played by Arthur Christiansen, who was the real-life editor of the Daily Express from 1933 to 1957. This fact, however, does also explain why Christiansen's performance is so agonisingly wooden.

In terms of performances, Stenning stands out as the film's protagonist; a divorced, washed-up former columnist with a drinking problem and no respect for punctuality. But whether a result of changing attitudes or a sign of an overloaded script, the character's boyish cheekiness comes across as more annoying and intrusive than charming or mischievous.

The times in which this aspect of the character does work is in his dialogue with veteran reporter Bill Maguire, played by Leo McKern. Maguire has some of the wittiest lines in the film and he and Stenning form an entertaining combination through their bickering and wise-cracks. Their friendship is perhaps one of the script's saving graces, although overshadowed by the extent to which the film appears to have little to say on the role of women in the event of an impending apocalypse.

In fact, while on this point, it is worth remembering that even Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, which had been released the previous year, depicts its female characters as strong individuals capable of deceit, intelligence and independent thought. It is not hard to see that the two-dimensional depiction of women in The Day Earth Caught Fire is probably more a failing on the filmmakers' part, rather than a sign of changing attitudes. Undoubtedly, Fleet Street was an incredibly male-centric industry in the 1960s – and many would argue that the world of journalism still is – but even so, this aspect of the film will jar with modern audiences.

Ultimately, The Day The Earth Caught Fire poses some interesting questions as to the right of humanity to go beyond the limits intended by nature, and aided by some strong performances. The open ending is also a nice touch, as it emphasises the unknown, ambiguous nature of human existence and the helplessness of a species attempting to divert the course of the planet on which it is travelling. While the film's strong points do not go far enough to save it on the whole, there is still enough to keep audiences entertained, and to explain why the film continues to resonate with audiences and filmmakers alike.

Iain Todd

A team of journalists at London's Daily Express are struggling to get to grips with a sudden and dramatic shift in the world's climate, following the testing of nuclear bombs by the American and Russian governments.

Washed-up alcoholic Peter Stenning, played by Edward Judd, and Bill Maguire, played by Leo McKern, are two reporters at the paper who attempt to get the story behind the phenomenon.

Stenning begins an infatuated relationship with Jeannie Craig, a secretary at the Meteorological Centre, played by Janet Munro. Using Jeannie as a spy, the newspaper discovers that the recent bomb testing has not only changed the Earth's tilt, affecting the world's climate zones, but has sent the entire planet hurtling towards the sun.

As mist descends on London town and the Thames begins to dry up, the journalists at the Daily Express, along with the rest of the world, must put their faith, and the future of humanity, at the hands of the scientists and experts who caused the catastrophe in the first place.

The Day The Earth Caught Fire excels as a cautionary tale about the desire for mankind to outdo nature, and the subsequent catastrophes that often befall such hubris.

Given that the film was released at the beginning of the sixties and around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, it is clear The Day The Earth Caught Fire was influenced by European anxieties of nuclear fallout caused by two warring superpowers, but also a more general scepticism about the right of humanity to meddle in natural forces that it doesn't truly understand.

Where the film perhaps falls flat, however, is in a quite-unavoidably male-centric perception of the world. Female characters seem only to perform secretarial duties at best; passing on information from man to man and rarely acting as knowledgable, independent people in their own right. Terms like 'sweetie' and 'dear' are used a little too often for comfort, while Janet Munro's character Jeannie is subjected to more than a few comments about her appearance that would today be considered downright sexist.

Chauvinism aside, the film gives an interesting and authoritative glimpse into the workings of Fleet Street hacks and print newsrooms at the beginning of the sixties, as the majority of the action and revelations are seen through the eyes of the journalists reporting on them. The dialogue is appropriately fast paced, as witty comment follows witty comment with the regularity of an Oscar Wilde comedy, if without the charm.

Part of the film's journalistic authenticity probably stems from the fact that the part of Jeff, the editor, is played by Arthur Christiansen, who was the real-life editor of the Daily Express from 1933 to 1957. This fact, however, does also explain why Christiansen's performance is so agonisingly wooden.

In terms of performances, Stenning stands out as the film's protagonist; a divorced, washed-up former columnist with a drinking problem and no respect for punctuality. But whether a result of changing attitudes or a sign of an overloaded script, the character's boyish cheekiness comes across as more annoying and intrusive than charming or mischievous.

The times in which this aspect of the character does work is in his dialogue with veteran reporter Bill Maguire, played by Leo McKern. Maguire has some of the wittiest lines in the film and he and Stenning form an entertaining combination through their bickering and wise-cracks. Their friendship is perhaps one of the script's saving graces, although overshadowed by the extent to which the film appears to have little to say on the role of women in the event of an impending apocalypse.

In fact, while on this point, it is worth remembering that even Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, which had been released the previous year, depicts its female characters as strong individuals capable of deceit, intelligence and independent thought. It is not hard to see that the two-dimensional depiction of women in The Day Earth Caught Fire is probably more a failing on the filmmakers' part, rather than a sign of changing attitudes. Undoubtedly, Fleet Street was an incredibly male-centric industry in the 1960s – and many would argue that the world of journalism still is – but even so, this aspect of the film will jar with modern audiences.

Ultimately, The Day The Earth Caught Fire poses some interesting questions as to the right of humanity to go beyond the limits intended by nature, and aided by some strong performances. The open ending is also a nice touch, as it emphasises the unknown, ambiguous nature of human existence and the helplessness of a species attempting to divert the course of the planet on which it is travelling. While the film's strong points do not go far enough to save it on the whole, there is still enough to keep audiences entertained, and to explain why the film continues to resonate with audiences and filmmakers alike.

Iain Todd

More info : http://www.bfi.org.uk/sci-fi-days-fear-wonder